THE READING BRAIN AND FIVE PILLARS OF LITERACY

By Kelly Gary

PWCA Board Director

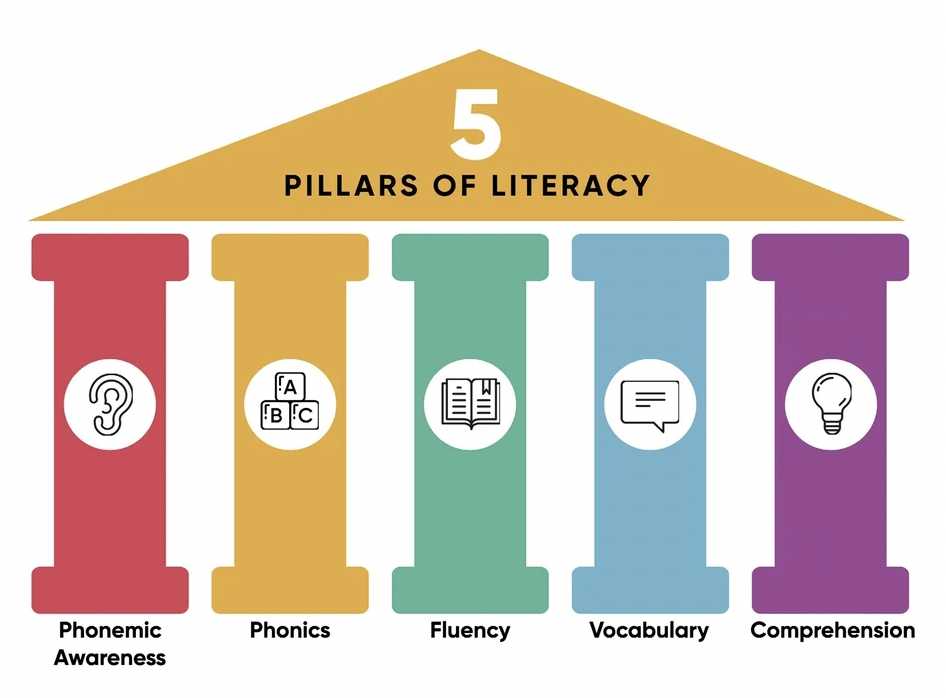

All the best things in life start with a strong foundation. The building blocks of reading, as defined by the National Reading Panel, include phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Learning to read is not easy. Actually, it is not even natural. There exists nearly four decades of scientific research around how children learn to read. These findings challenge the belief that children learn to read naturally. As teachers, we need to deliver tried and true, meaningful instruction that we know is successful at bringing at least ninety percent of students to grade-level reading. It has been said that at the most basic level, the essential purposes of teaching are love of content and love of students. Thus, preparing teachers by giving them the essential tools for and basic understanding of the reading brain is crucial in carrying out teachings’ essential purposes. An understanding of the reading brain is beneficial for teachers, parents, and students alike. This is why Hillsdale College provides its Member School teachers with a variety of resources and training opportunities. Great teachers combine their skills and knowledge from many years of training to teach for success. They understand how children learn. If not, then anyone could pick up a curriculum and deliver it by just following a script. Understanding the reading brain is an essential part of a successful approach to teaching.

WHAT IS THE READING BRAIN?

Neurons that fire together, wire together, and we can grow our brains with practice. Seidenberg (2018) notes that during reading, multiple parts of the brain are in constant collaboration and work together to process information. A speech to print approach is natural. Students hear and speak first.

Engaging students with phonological awareness activities before Pre-K trains the brain to listen to patterns orally. These multisensory activities get them ready for Phonemic Awareness and Phonics in K – 3rd where they are learning to automatically and fluently read words. Beginning in 4th, the student brain will have more room to learn complex vocabulary where reading to learn becomes more developmentally essential.

The speech-to-print approach allows for a more logical and complete understanding of how the American English system works; our 26 alphabet letters do not contain symbols for some speech sounds (approximately 44 sounds) that still must be represented (/sh/, /ng/, and others), and many letters often take on multiple jobs, or sounds, in our orthography, otherwise known as our conventional spelling system of spoken language.

In a speech-to-print approach, instruction builds knowledge from spoken to written words and begins with phoneme awareness. With this approach, students develop essential neural pathways in the brain that connect the visual word form area with spoken language. This strengthens word analysis for decoding. Once that mental process is ingrained, students have the cognitive ability to internalize many other complex letter patterns and sequences that they will see in print (Hoover & Tunmer, 2020).

FIVE PILLARS OF LITERACY

As we look to the Five Pillars of Literacy, a progression of skills builds these strong foundational components of successful reading instruction by shaping learners’ brains one step at a time, to learn to read and to understand the written English language. Structuring an effective and research-based literacy and language arts block is the first step to laying a good foundation for building students’ literacy skills. These five pillars work together to establish the foundation of an effective literacy instruction strategy.

1. Phonemic Awareness – The ability to hear, identify, manipulate, and substitute phonemes—the smallest units of sound that can differentiate meaning—in spoken words.

Meaning: Teaching phonemic awareness means instructing students to identify and manipulate the approximately 44 phonemes in the English language. It doesn’t require students to be able to read or even see printed letters to grasp this concept; it’s all about the sounds that word parts make. Essentially, students begin by learning individual phonemes, then joining phonemes, and finally, building words.

Why? Phonemic awareness is a strong predictor of long-term reading and spelling success. By using effective teaching strategies, phonemic awareness can be successfully taught during the literacy block. In instruction planning, it is also important to recognize that development of phonemic awareness must be quickly followed by the introduction of phonics. Research shows that teaching sounds along with letters of the alphabet helps students better understand how phonemic awareness relates to reading and writing.

2. Phonics – The ability to understand that there is a predictable relationship between phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (the letters that represent those sounds in written language) in order to associate written letters with the sounds of spoken language.

Meaning: Students begin to crack the code on reading. Phonics instruction teaches students how to build connections between sounds and letters or letter combinations and how to use those connections to build words.

Why? While the English language is full of irregular spellings and exceptions to phonetic rules, phonics teaches students a system for remembering how to read words so that they are able to read, spell, and recognize words instantly.

3. Fluency – The ability to read text accurately, quickly, and expressively, either to oneself or aloud; the NAEP Oral Reading Fluency Passage Reading Expression Scoring Rubric helps illustrate the learning progression of this skill.

Meaning: Fluency is the ability to read as well as one speaks and to make sense of what is being read without having to stop or pause to decode words. Fluency is different from memorization. Confusing fluency with memorization happens because students have read the text often and can repeat it without reading. Actual fluency is developed with the repeated, accurate sounding out of words.

Why? Developing fluency is critical to a student’s motivation to read. When students struggle to sound out letters and words, reading can become a laborious and exhausting task. Some students may begin to think of reading as a negative activity. As students begin to obtain words more easily, they should also practice dividing text into meaningful chunks, knowing when to pause and change intonation and tone. With guidance and feedback, students begin to recognize these cues during reading and develop deeper comprehension.

4. Vocabulary – The growing, stored accumulation of words that students understand and use in conversation (oral vocabulary) and recognize in print (reading vocabulary), or their lexicon.

Meaning: Since vocabulary is very closely tied to reading comprehension, it can be learned both orally and through text, or print. Most vocabulary is learned through everyday conversations, reading aloud, or independent reading. Children are unconsciously building their oral vocabularies all the time.

Why? In order to comprehend reading, students must understand the meaning of the words they are reading. Beginning readers use their oral vocabulary to make sense of words they see in print. If students encounter an unfamiliar word while reading, their reading comprehension is momentarily interrupted until the new word is added to their vocabulary. When taught explicitly using word-learning strategies, students can build a robust vocabulary and improve reading fluency and comprehension.

5. Comprehension – The ability to understand, remember, and make meaning of what has been read, thus, comprehension is the purpose for reading.

Meaning: Students with developed reading comprehension abilities can predict, infer, make connections, and analyze what is being read.

Why? Even before children become independent readers, they can begin practicing and developing comprehension skills when books are read aloud to them. Students who comprehend what is read are both purposeful and active readers; they use strategies to think about the purpose of what is being read and monitor their own understanding as they read. These strategies allow students to isolate and verbalize where there is a lack of comprehension, which, in turn, opens doors for them to apply specific strategies so they may attain new levels of understanding.

PREPARING FOR CLASSROOM SUCCESS WITH INCREASED COMPREHENSION

Part of the work to prepare teachers for successful literacy instruction in the classroom is giving them the knowledge of the reading brain along with the time-tested and effective tools and strategies. Building on literacy tasks from easier to more difficult and then breaking down the harder skills into smaller parts is beneficial for most students. Together this framework of the reading brain represents the purposeful and carefully planned sequence for establishing a crucial foundation for literacy, teaching reading, and increasing comprehension. After all, learning to read is tough, BUT with proper teacher training and support and by following the natural progression of foundational skills + phonemic awareness + phonics + fluency = vocabulary ALL students have an improved opportunity for reading comprehension.